In 2021, FutureProofing healthcare initiative launched a health policy index known as the African Sustainability Index. 18 African countries were studied and ranked across six vital signs. Nigeria ranked 14th with a total score of 44 over 100. The country’s low performance is a reflection of the poor state of the health sector and inadequate budgetary allocations to improve the sector. For instance, Nigeria spends 3.89% of its GDP on the health sector, a figure that is proportionately lower than the 5% suggested by the World Health Organization (WHO). Nine years to the 2030 sustainable development goals, Nigeria is still far behind in universal health coverage (UHC). According to the World Health Organization, monitoring UHC means focusing on two key aspects: i) the proportion of the population that can access quality health care and ii) the proportion of a population that spends a large amount of household income on health. This categorizes the focus on UHC into access and financing. In this article, health finance will be the Focus while the third article in this series will discuss access to quality care.

Based on the African Sustainability Index ranking, Nigeria is the 4th lowest country in health finance, with a score of 36. This indicates lapses in Nigeria’s current health financing model, primarily based on households’ out-of-pocket expenses, compared to the tax, health insurance, and donor funding-based models predominant in other environments. According to the WHO, for a healthcare financing model to be considered efficient, the population should not spend a large amount of their income on healthcare. Unfortunately, this is not the case in Nigeria.

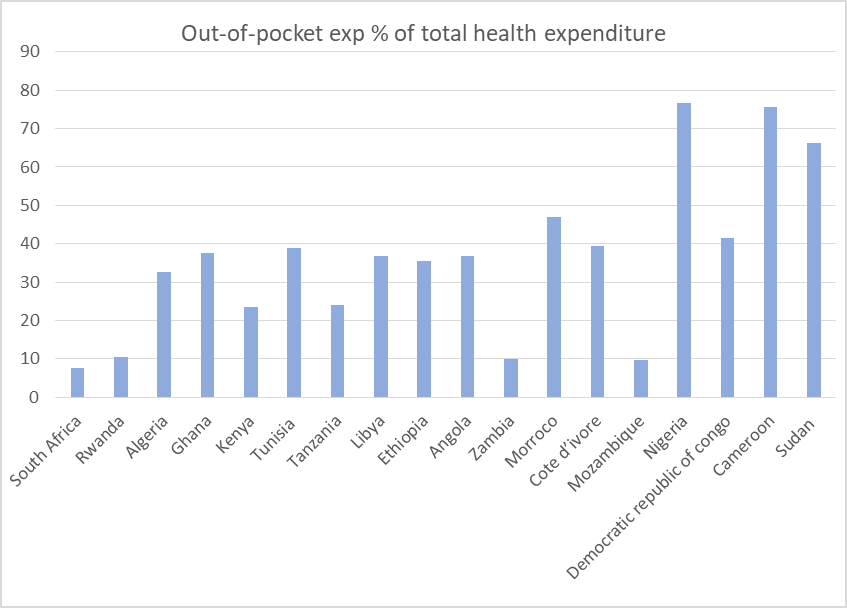

Health care in Nigeria is financed by mostly the out-of-Pocket model. About 69% of Nigerians finance their healthcare needs from personal savings or income. Regardless of their income, they have to pay for any health service rendered to them as well as the cost of drugs. The graph below shows the percentage of total health expenditure financed by out-of-pocket payment in the 18 African countries evaluated by the Future-Proofing initiative. The countries in the graph are placed according to their rank in the financing index. The graph shows that Nigeria has the highest level of out-of-pocket payment amongst the 18 countries. Although the graph does not show a clear relationship between out-of-pocket payment and position in financing, we can observe that the countries with an out-of-pocket rate above 50% are in the lowest rank of financing.

Out-of-pocket payment is a hindrance to health care given that over 40% of the population live below the country’s poverty line of $0.8 a day (World Bank, 2020). In fact, with the high rate of inflation, an additional 7 million people have been pushed below the poverty line according to a World Bank report in 2021. For instance, the cost of a complete malaria medication is $3 which is approximately 1500 naira. The hospital consultation fee varies between $2 and $50 depending on whether the hospital is private or government-owned. These costs, combined, outstrip the minimum wage of $53 and therefore beyond the reach of many. Government-owned hospitals which is usually the cheaper option would have been the solution to this dilemma but the financial burden is still higher than the estimated poverty indicator. The remaining 60% of the population living above the poverty line are not better off, they still grapple with high medical bills.

Recently, a growing number of the population is being financed by the National Health Insurance. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIC) was implemented in 2005 to pool health risks at the national level. The scheme is designed in a way that every member of the society irrespective of economic status would be covered. However, as of 2019, only 5% of the population were enrolled in the scheme. One reason for the low enrolment rate could be because the government has not made it mandatory for individuals in the informal sector. With Nigeria’s huge informal sector (about 70%), one can most certainly say that the scheme is inherently not mandatory. Even within the formal sector, some private employers do not provide basic health insurance coverage for their staff. Another factor that could contribute to the low enrollment rate is unawareness on the part of the populace. Some Nigerians, especially the uneducated populace are unaware of the insurance scheme. Some of those who have heard may not fully understand its implications and advantages over out-of-pocket payment. Hence, they may decide not to enroll in the scheme. In addition, apathy for government-run programs could contribute to the general low coverage in over 10 years.

Though relatively small, another source of healthcare funding in Nigeria is donor finances. These funds come from Non-Governmental Organizations, international organizations, faith-based institutions, and private donors. The donations often come in the form of medical equipment and consumables, drugs, blood banks, vaccines, and funds for hospital construction or renovations. These funds are often targeted at the poor and vulnerable and major disease-burden such as Malaria, HIV, Tuberculosis, Hepatitis, Cancer screening, and eye treatment. In as much as these donor programs have their impacts, they are generally inadequate and not readily available to cover the (infrastructure) financing gap in the health sector.

There is an urgent need for Nigeria to create a pro-poor health financing plan to bring about equity in the country’s health care system. This will entail more government involvement in health financing. The first step could be to optimize budgetary allocation to the health sector. In the Abuja declaration of 2001, African countries were urged to allocate 15% of their budget to the health sector. In the past 2 decades, Nigeria’s average allocation to health care is 4.67%. Eliminating financial barriers to quality and effective health care is another option to be explored. With the high poverty rate, risk pooling methods could be an effective method of eliminating the financial barrier. Insurance and tax-based financing methods are the top risk pooling methods of health financing. Although Nigeria already has the NHIS, more sensitization should be carried out to create awareness and encourage mass enrolment in the scheme. In all, effective health care finance is the first action towards revamping the entire health sector.

Tax based financing is the key learning point for me. I hope people in authority are paying attention.